“THE MOST ARRESTING SEQUENCE WE HAVE HAD SINCE JOHN BERRYMAN”: SIXTY SONNETS BY ERNEST HILBERT

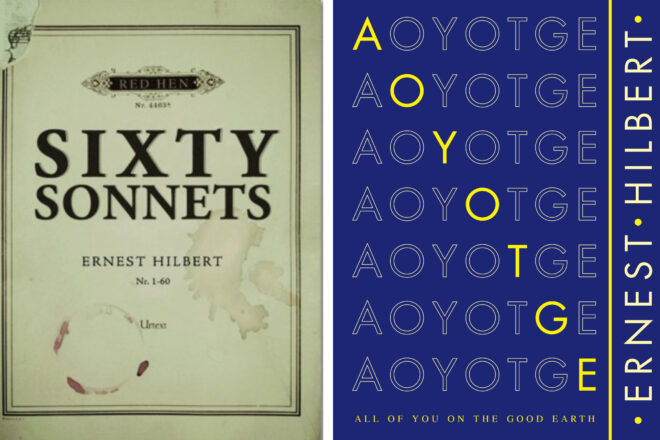

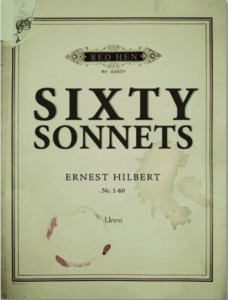

HILBERT, Ernest. Sixty Sonnets. Los Angeles: Red Hen Press, 2009. Small octavo, paper wrappers. $18.95. ISBN-10: 1597093610

Available from Alibris, Powell’s, Amazon, and Barnes & Noble.

“Hilbert’s sure-footed poems have the breathless urgency of a man telling others the way out of a burning building. Unafraid to startle, often winning out over recalcitrant material, they score astonishing successes. A bold explorer with few rivals, Hilbert enlarges the territory of traditional form. Sixty Sonnets may be the most arresting sequence we have had since John Berryman checked out of America” (X.J. Kennedy). “Like the minutes of the hour, these Sixty Sonnets both combine to make a whole and shine as individual moments. While groups of these sonnets occasionally suggest a narrative—refreshingly, like the fugitives and weary academics that people these pages—they work alone. The newspaper crime blotter itself, from which, perhaps, some of these incidents are torn, speaks up as a single sonnet. Here are barflies, high-school dropouts, retired literary critics, washed-up novelists and war-zone reporters, suburbanites and historians, and lyrics with a range of reference from Zippos and Star Wars figures to George Gissing and Thomas Eakins. Mostly in a decasyllabic line that allows for the roughed-up prose rhythms of speech, these sonnets tend to conclude in true iambic pentameter, the tradition that haunts rather than dominates these poems. It is the voice of a less lyrical Prufrock (‘We’ll head out, you and me, have a pint’), a voice that speaks with unsentimental affection for the failures, the ‘fuck-ups,’ the ‘Gentlemen at the Tavern’—but it is a voice that just as easily could be speaking of the gentlemen at the Mermaid Tavern, and indeed there is something of Marlowe, as well as Eliot, in this sensibility. The evasive presence in the background occasionally speaks in propria persona—the wry, worldly-wise voice of the poet himself—as much listener as talker—something like a sympathetic bartender, scrupulous in his measures, who has heard it all before, but nightly observes every hour unfold afresh from behind the counter” (A.E. Stallings).

“Hilbert’s sure-footed poems have the breathless urgency of a man telling others the way out of a burning building. Unafraid to startle, often winning out over recalcitrant material, they score astonishing successes. A bold explorer with few rivals, Hilbert enlarges the territory of traditional form. Sixty Sonnets may be the most arresting sequence we have had since John Berryman checked out of America” (X.J. Kennedy). “Like the minutes of the hour, these Sixty Sonnets both combine to make a whole and shine as individual moments. While groups of these sonnets occasionally suggest a narrative—refreshingly, like the fugitives and weary academics that people these pages—they work alone. The newspaper crime blotter itself, from which, perhaps, some of these incidents are torn, speaks up as a single sonnet. Here are barflies, high-school dropouts, retired literary critics, washed-up novelists and war-zone reporters, suburbanites and historians, and lyrics with a range of reference from Zippos and Star Wars figures to George Gissing and Thomas Eakins. Mostly in a decasyllabic line that allows for the roughed-up prose rhythms of speech, these sonnets tend to conclude in true iambic pentameter, the tradition that haunts rather than dominates these poems. It is the voice of a less lyrical Prufrock (‘We’ll head out, you and me, have a pint’), a voice that speaks with unsentimental affection for the failures, the ‘fuck-ups,’ the ‘Gentlemen at the Tavern’—but it is a voice that just as easily could be speaking of the gentlemen at the Mermaid Tavern, and indeed there is something of Marlowe, as well as Eliot, in this sensibility. The evasive presence in the background occasionally speaks in propria persona—the wry, worldly-wise voice of the poet himself—as much listener as talker—something like a sympathetic bartender, scrupulous in his measures, who has heard it all before, but nightly observes every hour unfold afresh from behind the counter” (A.E. Stallings).

First printing contains “pad” instead of “pat” on line 10 of page 44. The book’s first issue appeared with either glossy or matte paper wrappers, priority undetermined. The cover, designed by Jennifer Mercer, is based on that of a worn edition of Bach’s Klavierubung Teil Partiten issued by Edition Peters in 1950, from the collection of poet and critic Jan Schreiber. The tear at top left corner of the front wrapper displays the digitally-inserted musical staff from an engraved first edition of Domenico Scarlatti’s sonatas, intended as a hidden reference to the composer’s famous “sixty” sonatas. First issue, 21mm tall, .75mm thick (rather than 20mm tall and 1mm thick), matte buff wraps (rather than glossy beige).

SELECTIONS FROM THE COLLECTION

- “Domestic Situation” originally appeared in the American Poetry Review and was reposted by the Poetry Foundation

- “Prophetic Outlook” originally appeared in the American Poetry Review and was reposted at Best American Poetry and the Poetry Foundation

- “In Bed for a Week” appeared in The New Criterion

- “Fortunate Ones” originally appeared in the New York Sun and was reposted at Best American Poetry

National Poetry Out Loud (National Endowment for the Arts recitation program) finalists reading “Domestic Situation” from Sixty Sonnets.

Katianna Nardone 1 from RSM Distributors on Vimeo.

Clara Henderson 1 from RSM Distributors on Vimeo.

Victoria Howard 2 from RSM Distributors on Vimeo.

PRAISE FOR SIXTY SONNETS

Ernest Hilbert’s sure-footed poems have the breathless urgency of a man telling others the way out of a burning building. Unafraid to startle, often winning out over recalcitrant material, they score astonishing successes. A bold explorer with few rivals, Hilbert enlarges the territory of traditional form. Sixty Sonnets may be the most arresting sequence we have had since John Berryman checked out of America. – X.J. Kennedy, author of Lords of Misrule and editor of Literature: An Introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama

Hilbert has an appetite for life equal to his taste in literature: a rare combination in an age of dissociated sensibility. In these sonnets, whose dark harmonies and omnivorous intellect remind the reader of Robert Lowell’s, Hilbert is alternately fugitive and connoisseur, hard drinker and high thinker. But he is always a true poet, proud to belong to the company of those who still feel “The last, noble pull of old ways restored, / Valued and unwanted, admired and ignored.” – Adam Kirsch, author of The Modern Element: Essays on Contemporary Poetry

Just as the work of the modernists showed that the best free verse usually has something masterfully formal about it, Hilbert’s fine collection might serve to remind us that the best formal poetry has about it a marvelous colloquial freshness and inventiveness, and the ring of an actual human voice. It is a touching and intelligent book. – Franz Wright, recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for poetry

Sixty Sonnets delights in a decidedly badass bravura. Hilbert’s red-blooded diction and febrile subjects put paid to any lingering suspicions about traditional verse’s chronic anemia. His erudition is salted with humor, his romantic flights with a rage for order. He is a twenty-first century beatnik in Elizabethan ruff. A smashing debut! – David Yezzi, author of Azores and Birds of the Air

The American lyric rendered in these poems follows Coleridge’s description of the sonnet as “adapted to the state of a man violently agitated by a real passion.” Hilbert’s passion here is to contain, precious piece by precious piece, the unordinary quotidian of the American poetic. Sixty Sonnets is a gift to all of us from an exceptional ear and a fine consciousness. – Afaa Michael Weaver, author of Multitudes

For scale alone, the project at first seems improbable. But then you read, and it’s clear that Hilbert’s sensibility, bright-hued and gothic, sentimental, precise and ambitious, could be contained by no less. These wry and lovely poems are for anyone whose curiosity ranges from Petrarch to improv, and the result is a complex portrait of the America of our current era—composed in singing verse! – Dave King, Rome-prize winning author of the novel The Ha-Ha

Like the minutes of the hour, these Sixty Sonnets both combine to make a whole and shine as individual moments. While groups of these sonnets occasionally suggest a narrative—refreshingly, like the fugitives and weary academics that people these pages—they work alone. The newspaper crime blotter itself, from which, perhaps, some of these incidents are torn, speaks up as a single sonnet. Here are barflies, high-school dropouts, retired literary critics, washed-up novelists and war-zone reporters, suburbanites and historians, and lyrics with a range of reference from Zippos and Star Wars figures to George Gissing and Thomas Eakins. Mostly in a decasyllabic line that allows for the roughed-up prose rhythms of speech, these sonnets tend to conclude in true iambic pentameter, the tradition that haunts rather than dominates these poems. It is the voice of a less lyrical Prufrock (“We’ll head out, you and me, have a pint”), a voice that speaks with unsentimental affection for the failures, the “fuck-ups,” the “Gentlemen at the Tavern”—but it is a voice that just as easily could be speaking of the gentlemen at the Mermaid Tavern, and indeed there is something of Marlowe, as well as Eliot, in this sensibility. The evasive presence in the background occasionally speaks in propria persona—the wry, worldly-wise voice of the poet himself—as much listener as talker—something like a sympathetic bartender, scrupulous in his measures, who has heard it all before, but nightly observes every hour unfold afresh from behind the counter. – A.E. Stallings, MacArthur Fellow

Ernest Hilbert’s Sixty Sonnets is exactly what its title suggests—and thus it’s a performance as much as a book of poems, showy and spectacular. From the brisk noir of “She Remembers How They Fled from the Liquor Store Robbery in New Mexico” to the ironic call-and-response of “Fortunate Ones” to the elegiac fatalism of “White Noise” Hilbert takes the reader on a bravura run through seemingly every variation of tone and style that the sonnet can contain. It’s a craftsman’s book, a revival of form best summed up by the opening lines of “Song”: “A song for those who learn forgotten, slow / Skills, crafts submerged long past by massed commerce.” – Levi Stahl, poetry editor, Quarterly Conversation

[Sixty Sonnets] delivers the full range of human types and stories, and nearly the whole breadth of what the sonnet can do. . . . We might see Hilbert as being God in these poems—as taking the all-gathering view of the merciful God who has room for all these lost ones, right along with the desperate fugitives, retired literary critics, crime victims, lovers, and godfathers. The poet as indwelling creator spirit? It fits for Hilbert: poet, from poietes, maker. – Rattle

Hilbert is at once ironic, dark, and witty. [His] lines reflect our own precarious hold on the world, where we are always close to losing control. From the perspective of an intriguing mishmash of subjects, Hilbert often takes on the persona of the failed, the beat up, and the beaten down, in which all are “sinking on a soft black balloon.” Hilbert entreats his hapless heroes to “go on, get high,” though there is always a price to be paid. – Bookslut

The poems are beautifully made in their diction. The intelligence is clear. – Donald Hall

The only other poet who plies risk against reward so deftly is Pound. – Strong Verse

Ernest Hilbert, in Sixty Sonnets, reminds us how vigorous and fun a form the sonnet is. That the form is still fecund becomes abundantly clear when one sits down with this collection and reads four, seven, nine sonnets at a sitting. . . . These sixty leave one hungry for sixty more. – Library Thing

The reader must be prepared to leap from ancient Greece to the East Village in one or two lines, and familiar with the Oresteia as well as Metallica . . . his is a quicksilver mind, generous and open and humorous. – The Sheila Variations

Bob Dylan, another poet who often takes the fugitive as a persona, put it this way: “To live outside the law you must be honest.” That begins to explain, for me, [Hilbert’s] identification with people on the fringe, gangsters, drunks and women who return to the men who batter them. He’s acknowledging that the poet in this place and age is a person on the fringe. – Alfred Nicol, introduction at Newburyport Literary Festival

“Hilbert is one of our best rhymers since Robert Frost, and his poems have been compared by superb poets to those of John Berryman and Robert Lowell. We haven’t had a poetry like his—both seriously tough-minded and wryly self-chiding—to enjoy and mull over for a long time.” – Alice Quinn

“RAW ENERGY WITH ELEGANT AND ORIGINAL LANGUAGE”: ALL OF YOU ON THE GOOD EARTH BY ERNEST HILBERT

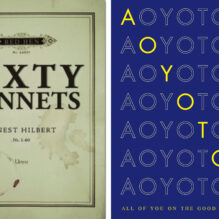

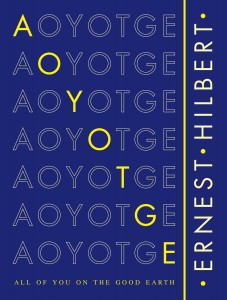

HILBERT, Ernest. All of You on the Good Earth. Los Angeles: Red Hen Press, 2013. Small octavo, paper wrappers. $16.95. ISBN-10: 1597092665

Available from Amazon, Amazon UK, Amazon Canada, Barnes and Noble, Powell’s Books, The Book Depository, Tower Books, BookADDA (India), URead.com (India), BiblioVault, Angus & Robertson (Australia), The Nile (Australia), Open Trolley (Signapore), Mighty Ape (New Zealand), SuperBookShop (European Union), Loot (South Africa), and better book stores. It is also available directly from the press itself.

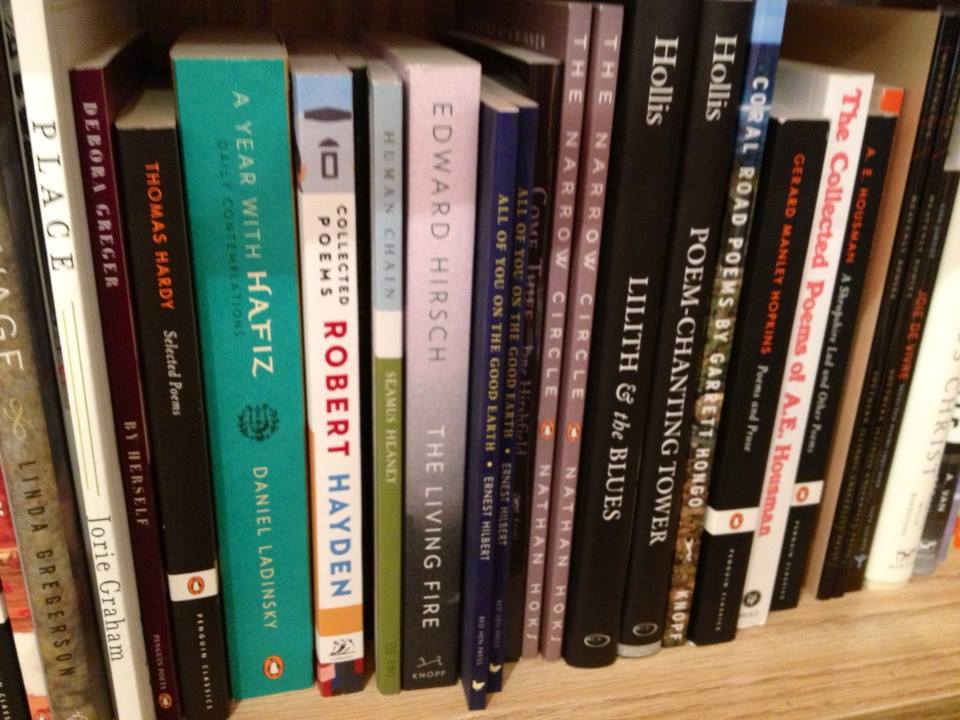

Ernest Hilbert’s second poetry collection, All of You on the Good Earth, explores the bizarre worlds of twenty-first century America first glimpsed in his debut, Sixty Sonnets, which X.J. Kennedy hailed as “maybe the most arresting sequence we have had since John Berryman checked out of America” and “whose dark harmonies and omnivorous intellect remind the reader of Robert Lowell’s,” according to Adam Kirsch. Critics have called Hilbert’s poems “at once ironic, dark, and witty,” containing the “full range of human types and stories, and nearly the whole breadth of what the sonnet can do,” “spectacular,” “both seriously tough-minded and wryly self-chiding,” concluding that “the only other poet who plies risk against reward so deftly is Pound.” Poet and critic David Yezzi salutes Hilbert as “a twenty-first-century beatnik in Elizabethan ruff.”

Ernest Hilbert’s second poetry collection, All of You on the Good Earth, explores the bizarre worlds of twenty-first century America first glimpsed in his debut, Sixty Sonnets, which X.J. Kennedy hailed as “maybe the most arresting sequence we have had since John Berryman checked out of America” and “whose dark harmonies and omnivorous intellect remind the reader of Robert Lowell’s,” according to Adam Kirsch. Critics have called Hilbert’s poems “at once ironic, dark, and witty,” containing the “full range of human types and stories, and nearly the whole breadth of what the sonnet can do,” “spectacular,” “both seriously tough-minded and wryly self-chiding,” concluding that “the only other poet who plies risk against reward so deftly is Pound.” Poet and critic David Yezzi salutes Hilbert as “a twenty-first-century beatnik in Elizabethan ruff.”

All of You on the Good Earth guides the reader through chambers occupied by visionary gravediggers and spaced-out movie stars, frenzied dropouts, sullen pirates, and unrelenting stalkers, noble war correspondents and cornered dictators, unlucky drunks and supercilious scientists, impatient goddesses and sad sea monsters, self-indulgent denizens of Plutonian strip-clubs and earnest haunters of ancient ruins, the infamous Rakewell in TriBeCa and sea nymph Kalypso in a beach house at the Jersey shore, characters wandering an America demoralized by economic decline. These poems contain fasts and feasts, laments and love songs, histories, fantasies, and elegies, the amusing and heartbreaking debris of life on this world, all the while recalling Seneca’s dictum, non est ad astra mollis e terris via (“the road from the earth to the stars is not easy”). The poems in its pages first appeared in Parnassus, Harvard Review, The London Magazine, The Yale Review, Poetry East, The Oxonian Review, Georgetown Review, American Poetry Review, New Criterion, Dark Horse, New Ohio Review, RATTLE, Cimarron Review, and 66: The Journal of the Sonnet. The cover is designed by Jennifer Mercer, based on the cover of the first edition of Ted Hughes’ collection Lupercal, published by Faber & Faber in 1960. The book’s front panel is also an homage to the legacy of the 1970s São Paulo Brazilian Noigandres “poesia concreta / konkrete poesie / concrete poetry” movement. First issue, .75mm width (rather than .5mm), matte wraps in lighter shade of Dignity Blue, 6804 (rather than glossy wraps in the darker Honorable Blue, 6811).

These sixty new sonnets find Ernest Hilbert, “an earnest / Pilgrim of some kind,” charging up to the ruins of a shared and personal past as well into the ether of his own (mostly) earthbound head. Part shaman, part showman, he reaches his hand in, winks, and, with a flourish, produces one little marvel after another. Like Lowell before him, Hilbert has found in the sonnet a form of confinement that excites and accommodates a liberality of temperaments, rhetorics, bad thoughts, and big ideas, but where Lowell favored blank verse, Hilbert surprises with rhymes he unwinds with preternatural finesse. His material ranges from the all too familiar to visionary moments in which our debauchery brings us to “fall apart like ancient stars” or to witness a vaseful of stargazer lilies “unfastening like a vast nebula” with a “long pour of poisonous gas.” Retrospective, forward-looking, tonic and toxic, All of You on the Good Earth is a wonder of a book, and Hilbert’s best yet. – Timothy Donnelly, author of The Cloud Corporation

Hilbert has written poems of superb lyricism. It’s hard to think of another poet with such range, and indeed with such brilliant delivery. Beauty, trash, exaltation, and humor are contained in his capacious and exacting forms. These are, quite simply, original and essential poems. – Justin Quinn, author of American Errancy: Empire, Sublimity, and Modern Poetry

* * *

The comparisons to Lowell are just . . . What’s so attractive here is the colloquial nonchalance that transpires within the formal decorum. It’s quirkier, more low to the ground, more hip, as one said in the olden days. “You should know I’ve come to terms with weather / Since you left.” This made me laugh out loud. – James Longenbach, author of Modern Poetry after Modernism

* * *

Hilbert’s debut, Sixty Sonnets made him something of a “bad boy” among the decorous New Formalists. The sonnets were saturated in alcohol, violence, literary allusion, and urban squalor; in them, muggers rub shoulders with fading academics. (Hilbert is neither, but perhaps on the outskirts of both highway robbery and scholarship: an antiquarian book dealer.) The 2013 All of You on the Good Earth sealed his promise as master of the modern American sonnet, but pushed his range of subject matter: all the brows—high, middle, and low—Science Fiction, pop-culture, academia, the TLS, Philadelphia neighborhoods, World War II, the Cold War. “Zeppelin” in a Hilbert poem could easily refer to either Count Ferdinand Von or Led. – A. E. Stallings, author of Like: Poems

* * *

Hilbert’s sonnets recall a range of work from Baudelaire and Robert Lowell to Henri Cole. Baudelaire counterpoints the formal perfection of the traditional French sonnet against nightmare-scapes of 1850s Paris to embody that tension within himself which lends the title to the longest section of Les Fleurs du Mal : i.e., Spleen et Idéal. Lowell’s blank verse sonnets generally maintain the English-language sonnet’s traditional iambic pentameter, though often roughing the meter up and abandoning rhyme in order to express a similar tension between the extra-temporal ideal and history’s broken reality. Henri Cole, especially in the breakthrough books The Visible Man and Middle Earth, uses an un-metered and unrhymed 14-line “sonnet” to enact similar tensions between abstract perfection and material imperfection, the life of the mind and the life of the body. – The Hopkins Review

* * *

“Genes clarify the genius and the freak / And prove we descend from a feral band,” Ernest Hilbert writes in “Outsider Art,” and there is no mistaking the “feral” appetite and intensity of these poems, or the bitter depths of experience they sometimes explore. What makes All of You on the Good Earth such a rare collection, however, is the way Hilbert unites that raw energy with elegant and original language, creating a style that sounds like no one else’s. – Adam Kirsch, author of The Modern Element: Essays on Contemporary Poetry

* * *

When a formal poem is doing its job well, it couldn’t exist in any other way. In All of You on the Good Earth, Ernest Hilbert takes on the sonnet form with every poem. At their best, Hilbert’s poems use that form to full advantage, revealing depths of meaning that would otherwise remain inaccessible . . . . If you’re interested in formal poetry—or even if you’re not—do yourself a favor and check out Hilbert. With work appearing everywhere from American Poetry Review to Yale Review to B O D Y to Rattle, he’s poised to become a major voice in contemporary formalism. – Cleaver Magazine

* * *

As the title implies, AOYOTGE is Whitmanesque in its embrace of the multiplicity of experience. Yet, to note as much is to note only half of the book’s ambition; the other half is the evocation of the “Good Earth” itself. Poem after poem presents us with a solitary figure in a landscape, and it’s in addressing not only the people on the earth, but their relationship to it, that Hilbert is at his most lyrical and memorable. – Hopkins Review

* * *

In his debut collection, Sixty Sonnets, Hilbert establishes a variation on the sonnet form, employing an intricate rhyme scheme and varied line length. A skillful practitioner of form and nuance, Hilbert shifts between delicately sonic moments and humorous narrative sequences. Hilbert’s second collection, All of You on the Good Earth, returns to his idiosyncratic, highly inventive sonnet form. – Poetry Foundation

* * *

There is an essential kindness in Hilbert’s poems, a humanity of perspective that treats even its most abject subjects with humor and empathy, regardless of their foibles. But what makes Hilbert’s poetry great—what gives his poems their power—is his sheer mastery of poetic form. . . . These are poems of real depth and resonance, gorgeously constructed and brilliantly executed. . . . It is refreshing to read poetry that doesn’t have to bullshit about what it is. Hilbert can write a sonnet that sounds so natural—and so casually American—that heard aloud, one might not even recognize it for what it is. Or rather, one would recognize it for exactly what it is: great poetry. – Joshua Mensch, B O D Y Magazine

SELECTIONS FROM THE COLLECTION

- “Dusk in a Crowded Train Compartment, Regretting My Life” originally appeared in the American Poetry Review and was reposted on the Best American Poetry Website

- “Pirates” appeared in The New Criterion

- “Ashore” appeared in the Yale Review, reposted at E-Verse

- “While You Were Out” with audio by X.J. Kennedy appeared in LineBreak.

Ernest Hilbert has written some of the most elegant poems in American literature since the loss of Anthony Hecht. A fascinating blend of the Augustan and romantic (an Augustanism that flirts with the sweaty Rochester as much as the marmoreal Johnson, and a romanticism charged with as much street grit as lyricism and longing), with a cadence that can be as wickedly eloquent as Lowell or compressed, as an elegantly held fist, as Bishop, Hilbert holds tight to an understanding of poetry and the role of the poet—proud without complacency, authentic without cheapness, self-respecting and self-mocking—that is (thank God) not particularly popular in poetic circles today. . . He, or his poetic persona, moves across the world, an “earnest pilgrim,” from the necropolis at Vulci to Iwo Jima, to the bars of TriBeCa and the back alleys of Queens, to Senecan Rome, “from Grub Street to the Brill Building,” to the “dark suburbs” (“The insatiable sprawl thieves as it gives,” as he says in a memorable line in a book packed, jammed, and o’erbrimming with lines you will want to linger over, savor, like the wines of Helicon), to New Jersey’s Mullica River, to a graveyard in Philadelphia . . . Any page you open to contains, not a gem, but a treasury, a manuscript of illuminations, lapis lazuli and gold, even when the poet is watching his key chain spatter down a toilet bowl in a late New York club night. He describes, like a Milton cast away in the alleys, what he sees on a bleak night in the slums of a great, wounded city, or in the hungover misery of a bus ride down the east coast’s suburban sprawled flank, in a poverty-stricken childhood home life among “the peculiar clan at cul-de-sac’s end,” in the fissile fossilizing of a convention of archaeologists, in a list (far from incomplete) of America’s robust negatives, in a pixilated Oscar acceptance speech, and a rancid envy’s tongue lashing of revenge—all without missing a beat or a foot. – Christopher Bernard, Synchronized Chaos

* * *

[All of You on the Good Earth] is filled with gritty, vibrant, technically innovative and masterful poems that speak directly to how we live now. They’re dark, they’re funny, they can be quite tender, and they always observe the world closely. – Conundrum Best Books of the Year 2013

* * *

Looking forward to a new generation of poets coming of age, I love reading Ernest Hilbert’s recent work. I want to say, probably to his amusement, that he writes as a man who has woken up at the tail of a great snake. His mastering of the form of the sonnet to describe that situation sets a foot on a spiritual ladder of sorts. I cannot help but allegorize Hilbert’s poems when I read them. They seem so true, literally speaking; their well-wrought forms also suggest hidden depths of meaning. His poems are often plunged in the “sluggish murk” of our seemingly bottomless modern Hell, which Lady Macbeth perceived prophetically in her sleep, and “pulled toward the sea” of time and space, but they also strive, almost earnestly, in the opposite direction, and that tension makes them true, good, and beautiful. Like the charioteer in Plato’s Phaedrus, Hilbert is in control of two kinds of winged horses: one “noble and of noble origin,” the other “ignoble and of ignoble origin.” He has been described as “part shaman, part showman,” and I more than half-believe in the generosity of Hilbert’s poems. They begin to take care of those whom King Lear had forgotten during his opulent reign, although mostly it is the poet himself who wakes up broken-hearted and sometimes literally beaten. – Edward Clarke, The Spirit of Poetry

* * *

From brown waters cramped with bits of boats and ghosts, to apartments clouded with drug dust, and skies filled with lumbering zeppelins, Hilbert’s poetic stance is a satellite in action; his poems orbit the globe capturing (in high-res) the grime, sublime, and everything in-between. Hilbert’s poetic prowess shines brightest when his lines are coated in darkness. “Sailing the Mullica River (Great Bay Estuary) 1978” sends the reader downriver atop waters “housing ghosts and unseen summers in shadow.” With his father, an old sailor himself, the speaker witnesses “clouds dyed and bruised like the sea.” Black mud stirs below their traveling vessel. Images like these, while beautiful, are dabbed with gloom. Hilbert excels with a somber palette—especially when he’s painting lines of the seafaring sort. “Ashore,” depicts a “harpooned great white shark” who’s washed up on the beach—dead. A crowd gathers to inspect the body. Hilbert is quick to remind the reader that, beneath the waves, lies “slit sails, drowned crews, [and] split hulls.” Setting aside visions of oceanic romance, Hilbert exposes the sea’s subtle haunting humanity. It’s a visceral must-read sonnet. But let’s not get too serious. Ernest Hilbert can have fun. Of all Hilbert’s poems in All of You on the Good Earth, there’s nothing like “Sunrise with Sea Monsters.” As a love letter to Ray Harryhausen (American producer and visual effects pioneer who created films like It Came from Beneath the Sea), the poem is a huge success, but it’s also something more. “The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms skulks/Ashore, hearing a foghorn, lonely for friends” writes Hilbert who also mentions the “clumsy frogman from the Black Lagoon” and “Nessie.” These are set pieces that, despite their hilarity, make us feel for these ugly mugs. They’re “[b]eaten back by ray guns, germs, and Marines” as sea gulls peer into the ocean “watching for the next poor monster.” We almost revel in their destruction. This rare moment shows that Hilbert can be humorous, albeit the dark sort. Hilbert supplies us with poems like “Nights of 1998” to keep things fresh. There’s an intense party happening downtown (drugs, drinks, fights, and puke included) in the speaker’s apartment and he’s attempting to make sense of the unfolding mayhem. “I’m lit like a war,” he says. What a fantastic line. “We fall apart like ancient stars, sparks— / Gold like pollen blown across all this dark” writes Hilbert. Suddenly, I’m back in space, watching the Earth, Ernest Hilbert’s Earth, rotate wonderfully, horrifically on. – Apiary Magazine

* * *

[Hilbert’s] that rare thing these days, a sonneteer, but he brings a conversational vibrancy to the form that continually pushes against its constraints even as it draws strength from them. And, oh, the pleasures he takes in sound and rhythm and rhyme! “Taped up, damp now, smeared photo of the stray / On each scratched steel lamppost along the way.” – ivebeenreadinglately.com Book of the Year (Poetry), 2013

* * *

The point is all-inclusiveness, acceptance of the whole world of subject matter. [All of You on the Good Earth] means to take in the beautiful and the awful, and it does; its publicity tells us that it “continues to explore the bizarre worlds of twenty-first-century America.” The attractive cover design, purely color and text, avoids any interpretive tilt, neither approving nor condemning that bizarreness. The index of the book’s cultural references runs from Alighieri to Zevon, through Nick Cave and Montaigne and Wilde and assorted others on the way. To get everything here, the reader needs to be able to parse a little Latin and a little Italian and have a purchase on most of Western history, poetry, movies, and television. The breadth is consonant with the list of accomplishments in the poet’s bio. The small, witty touches that enlivened Hilbert’s first book are here too—for example, the sly statement on the copyright page that resemblances to actual persons are ‘of course, purely intentional.’ Close observation in all things, low or luxuriant, is the great strength of the poems . . . The best we can do with the sad strangeness is to look carefully and take the marvels where we find them, admitting that they never finally wipe away the tears of things. . . . It’s a poetic stance we can believe in the twenty-first century. It’s a significant one, in a poetic world that has become, in David Yezzi’s phrase, “like a spayed housecat lolling in a warm patch of sun.” Hilbert’s is a voice we can trust and be grateful for as a way of making sense of this bizarre, and sad, and laughable—and good—Earth. – Angle, Journal of Poetry in English

* * *

Ernest Hilbert’s second collection of poetry, All of You on the Good Earth, is an enlightening example of the revival of the sonnet. The poems are intelligent, topically indulgent, and extremely well crafted. The sonnets are capsules, compressing large ideas or expanding small ones, lined up in equal measure. – New Pages

* * *

Hilbert is masterful at rhyme. This is not over-the-top praise; his technique is simply awe-inspiring. Reading this and the rest of the poems in this collection, a reader will mostly be unaware of his tremendous craft and only after search and analysis will his strict formalism become apparent. Nothing he does is obvious, his rhythmic constraints are unfelt, all of his seams are hand-sewn yet flawless and undetectable. – Philadelphia Review of Books

* * *

Hilbert insists that perspective, where and how we are when we observe, is everything . . . . Just as Hilbert observes his modern world, he also reflects on the past, not his past, but that of humanity. He does so as if he were there, as if he were able to time-travel and seize these moments for future examination. A denizen of the present and an admirer of the past, Hilbert doesn’t overlook the not-so-pristine images of industrialism or modernity, but he also does not herald the great histories. Instead, he delves into both, mixing old and new, reaching for truth as he sees it, using one of the most classical literary forms, each sonnet a small window looking out to the larger view. – Glassworks